Mathew Brady - Mathew B. Brady Biography (1823-1896)

Whether you know his name or not,

you've seen Mathew Brady photographs. Mathew Brady is one of the best-known

photographers, both in his time and in ours. He was a highly successful portrait

photographer who essentially invented documentary photography and

photojournalism, and he contributed significantly to our understanding of the

U.S. Civil War. Nevertheless, he ultimately sacrificed his wealth, his

livelihood and his health for his art and died impoverished and

underappreciated.

Mathew Brady learned the new art of

photography as a teen from inventor Samuel Morse. He quickly perfected the

daguerreotype process and opened a portrait studio to much acclaim on Broadway

in New York City in 1844. He convinced many of the most powerful and famous

people of the day to sit for his portraits, including presidents, political

leaders, businessmen, writers, military generals and more. He was a master at

marketing his craft, luring buyers into his studio by lining it with portraits

of the social and political elite and calling it a "Hall of Fame." Far more than

just a business venture, Brady felt photography was his calling and it was his

duty to historically document the people who were shaping America. He became one

of the first people to document history with the camera. After winning the

presidential election, Abraham Lincoln even credited the distribution of Brady’s

carte de visite portraits of him for winning the election.

|

|

|

|

|

Cornelius Vanderbilt from a

daguerreotype by Mathew Brady |

Mathew

Brady's Portrait Gallery

Broadway and Tenth Street in New York City |

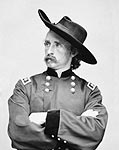

Civil War

General George A. Custer from a wet collodian glass negative by Mathew

Brady |

In 1861, at the height of his

career as a portrait photographer with several large studios and a considerable

fortune, Mathew Brady turned his focus to the Civil War. He later said, "I had to go. A

spirit in my feet said 'Go,' and I went." He hired 18 photographers, supplied

each of them with a full wagon photographic studio, and set out to document the

realities of war. Photographers such as Alexander Gardner, and Timothy O’

Sullivan took on the job. Along with Brady, these men are now regarded as early

masters of photography. While his photographers documented most of the

war, they were under contract to attach Brady’s name to every image taken. Brady

sank all of his energy, his fortunes and ultimately his health into the cause of

documenting the Civil War in photographs. He’s said to have spent over $100,000

on the effort, at a time when the average American made $300 a year.

|

|

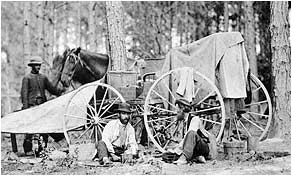

One of the Mathew Brady photo crews outside of Petersburg, VA.

|

In 1862 Mathew Brady presented his

photographs from the Battle of Antietam to the public in New York City,

entitling the exhibition "The Dead of Antietam." For the first time, average

citizens saw the carnage of war. Since the photos required long exposures, the

photos captured the moments before and after most of the action. The public saw

the vibrancy of life in the faces of those prior to battle, juxtaposed with the

gruesome images of contorted corpses on the battlefield. The New York Times

commented, “If he [Brady] has not brought bodies and laid

them in our door-yards and along our streets, he has done something very like

it.” While traditional journalists were sending tales filled with

half-truths romanticizing the war, Brady’s photographs spoke an undeniable and

never before witnessed truth about how destructive and grotesque war is.

Civil War Photos by Mathew

Brady and His Team of Photographers.

|

|

|

|

|

Union observation balloon. |

Soldiers of 4th New York heavy

Artillery loading 24-pdr. siege gun. |

Battlefield at Antietam on the

day of battle. This is the only known photo during a battle of the Civil

War. |

|

|

|

|

Ambulance drill in the field. |

1st African American infantry

unit. |

Civil War Confederate

casualties at Antietam. |

After the war Mathew Brady found that

people preferred to forget the war, and his expectation that his war photographs

would be treasured and reap him financial reward proved elusive during his

lifetime. Within a few years, he was forced to file bankruptcy. He eventually

sold his glass negatives of the war to the United States government and received

a grant from Congress for the rights to his photographs. His total take of just

over $25,000 wasn’t enough to cover his debts. By the time of his death in 1896,

his contributions to photography and the documentation of U.S. history were

recognized, but certainly underappreciated. His glass negatives in the hands of

the government had been allowed to severely degrade, and a majority of the

collection had been split up and sold off. He died poor and in relative

obscurity.

Today we more fully

recognize Brady's contributions to photography, journalism and history. The

majority of his images have been acquired by the Smithsonian Institution and the

U.S. Library of Congress in Washington D.C.

Buy a Mathew Brady Collection Photo

We offer a broad selection of

Mathew Brady photos on our website that we have

painstakingly restored to remove significant dust, scratches, and in many cases,

cracks in the original glass plate negative. We're also happy to print the

original un-restored image on request. If you’re interested in another photo by

Mathew Brady, just

contact us.

We have hundreds of images currently in the editing and restoration process and

have access to much more of the Brady Collection.

Robert's Recommended Websites on

Mathew Brady:

“Mathew Brady’s Portraits,” from The

Smithsonian Institution’s National Portrait Gallery

This is a very impressive site from

the Smithsonian’s National Portrait Gallery. You can go through Brady’s virtual

gallery, read about the subjects of each of his photographs, and learn how Brady

and his contemporaries made photographs (long before Kodak, this required a

wagon full of chemicals and equipment).

Mathew Brady Bio on Dickenson

College Website

A pretty good essay, presumably by a

student at Dickenson College

“Brady’s Portrait of Grant,” by Jeff

Galipeaux

Great piece on Brady inventing

candid portraiture in June, 1864, when he captured a candid (or more

specifically awkwardly posed) shot of General U.S. Grant in the field.

And if you need more online

material, there's always Google:

Robert's Recommended Books on Mathew Brady (these open a new window to

Amazon.com):

If you found this article interesting, you may also want to join Robert's

monthly newsletter. Each month he features a particular historically significant

photographer, introducing you to that person's work and how the person has contributed to the world of photography. You'll also get free access to our screensavers, exclusive discounts,

and updates on our newest additions to the RMP Archive. Enter your email address

in the form below.